When post-doctoral fellow Marie-Thérèse Bammert met Semir Beyaz, Assistant Professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, at a conference in 2024, she was still in the midst of her graduate work in Germany. Her research examined the progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a chronic condition that causes progressive scarring and thickening of the lining of the lungs. The root causes of the disorder are unknown, but as Bammert explains, the condition encourages a persistent state of inflammation, which is normally a healthy but temporary response to acute injury or illness.

“I believe this is directly translatable to endometriosis,” Bammert explains, “because we have a similar scenario: chronic inflammation of unknown origin.” Bammert’s graduate work yielded insights into how specific epigenetic factors can amplify the activity of genes that promote fibrosis and chronic inflammation.The insights she gained into the specific factors that cause persistent inflammation and lead to fibrosis in lung tissue formed a natural bridge to the work she’s doing now on the underlying causes of endometriosis. Today, her primary focus is on understanding why ectopic endometrial glands and stroma (the cells that cause endometriosis) get cleared in some patients but persist in others and form painful lesions that can travel to distant sites in the body.

By the time Bammert joined Dr. Semir Beyaz’ group at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) last summer, Dr. Beyaz’ research efforts were deeply invested in the biology of the endometrium and in untangling the basic mechanisms of endometrial cancer. Bammert and Beyaz followed parallel threads in their work from basic immune biology to epigenetics and epithelial cell function, linking epigenetic changes to chronic immune activation and disease.

Dr. Beyaz, who today serves as lead investigator at CSHL, was inspired to pursue a PhD in immunology at Harvard after gaining firsthand exposure to clinical immunology at Massachusetts General Hospital. In looking at specific types of immune cells and how they survive harsh environments and contend with pathogens, he found that he was fascinated by the immune system but wanted to step back and look at something more fundamental; for one, the complex genetic and epigenetic interactions that underpin the development of different cellular and physiological traits and how they operate in health and disease.

After shifting toward genetics and epigenetics during his PhD, Dr. Beyaz was compelled to take one further step back to study the behavior of epithelial cells—cells that are unique in their capacity for regeneration and renewal and form the delicate but richly complex linings of our organs, including the endometrium. He focused on how diet affects the presence of fatty acids in the gut, finding that a high intake of processed foods, sugars, and fats can engage epigenetic programs that push these cells in the lining of the gut from a normal regenerative state toward a state of unchecked growth that more closely resembles cancer.

“The cells in our body don't live in isolation,” says Beyaz. “They are actually in very close harmony in the tissue, and those genetic and epigenetic mechanisms affect everything together in that harmony.”

In 2024, Beyaz attended a medical conference organized by the Endometriosis Foundation of America (EndoFound), where he met Dr. Tamer Seçkin, a minimally-invasive surgeon globally recognized for setting standards of patient care for endometriosis. The two converged around their passion for addressing an illness that affects millions of patients whose pain and symptoms are frequently dismissed and neglected in the broader medical community, routinely delaying diagnosis for years. Before long, their conversations centered around the actionable synergies that could be achieved between basic research and clinical practice when it comes to endometriosis diagnosis and care.

For her part, when Bammert joined the lab as a postdoctoral researcher last summer, she hadn’t planned on coming to the US after finishing her PhD. But she was also moved by a powerful vision for change in the state of basic research into women’s health.

“I care a lot about how basic science can change lives,” Dr. Beyaz says, “and I’m a strong believer that if you want to change lives, you need to go through basic science,”

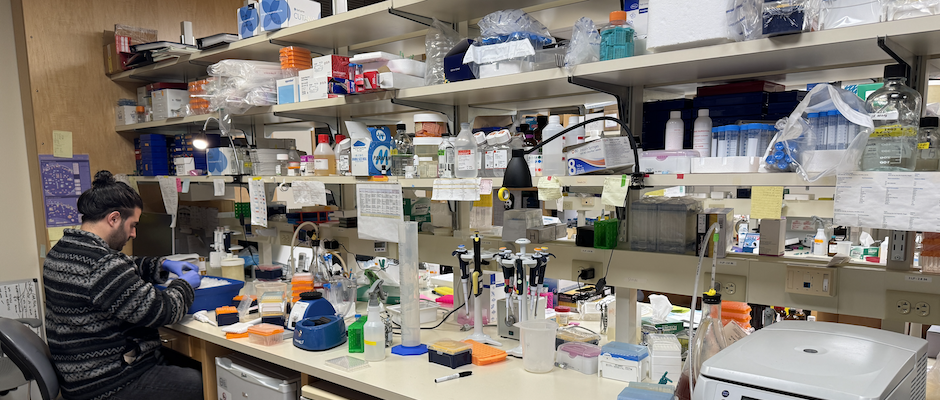

The Seçkin Endometriosis Research Center for Women’s Health at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory was born of this common vision in May of last year, supported by a 10 million dollar partnership with EndoFound. In the short time since its establishment, the lab has already made incredible strides in developing genetic, epigenetic, and molecular maps of cells from endometrium and endometriosis lesions, as well as finding innovative ways to model the disease in the lab that allows them to study the behavior of the tissues, their responses to changes in the environment, and eventually how they may respond to treatments. Knowing the genetic identities of these cells and how they’re regulated will also provide pre-clinical touchstones for diagnostic markers that will allow for faster, more precise, and less invasive diagnostics than the current field standard of surgery.

One of many challenges facing basic biomedical research into endometriosis is the lack of a good model system in which to study the disease in living tissue. The go-to animal model in research is the mouse, but as Dr. Beyaz explains, the unique cyclic shedding and regeneration of the endometrium that occurs during menstruation doesn’t exist in mice. Likewise, it’s impossible to gain a full picture of the complexities of endometriosis in other cell culture models, which are good at probing the dynamics of cells in isolation but fail to capture interactions that occur between living cells and tissues in the body.

To approach this problem, the group at CSHL has begun to take advantage of the rapidly advancing technology of organoids, which are three-dimensional tissue culture systems that can be grown in a lab using cells derived from patient samples. As Bammert describes the process, they’re establishing models of “endometriosis in a dish,” to investigate both normal and healthy endometrial tissue in a lab setting. Bammert had previously worked with lung organoids, and Beyaz’ group had already begun to establish a model that resembled early endometriosis.

Dr. Beyaz has a strong background in working with the kinds of molecular databases needed to build up organoid models of endometrial tissue. In 2021, he led a collaborative effort across multiple institutions, funded by a grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, to profile samples of endometrial tissue from patients across a range of diverse ancestries and backgrounds, particularly among groups who have historically been underrepresented in biomedical research. Across samples from 62 patients, they generated a molecular dictionary of gene expression at the cellular level, forming the genetic and epigenetic building blocks of a profile of endometrial tissue on a spectrum from healthy to tissue expressing disease.

A big advantage of organoid models over traditional model systems for disease is that while mice and cells can provide a general picture of disease pathology, organoids can give researchers deeper insights into gene expression and tissue interaction under specific conditions and at different timepoints through the progression of the disease. To delve deeper into these unique genetic signatures of endometriosis, the team at CSHL is leveraging spatial transcriptomics, a molecular technique that has flourished in recent years and opened an unprecedented window on the identities and functional organization of cells within tissues.

It’s important to understand which genes are expressed in specific tissue types in order to identify potential targets for therapies. But it’s equally important to know exactly where in a tissue or in a whole organ these genes are expressed so that research can understand how gene expression affects interactions between cells in a living organism. Spatial transcriptomics gives researchers the power to visually map these patterns as they occur within the landscape of organs and tissue structures, rather than more traditional techniques that can only tell them whether or how much a gene is expressed within a whole sample. The anatomical arrangement of this expression is invaluable for learning how cells find each other in both healthy and unhealthy tissue systems.

Beyaz also notes a new momentum in interest from pharmaceuticals, biotech, and academic research labs in endometrial, ovarian, and uterine health. Federal funding from the National Institutes of Health has risen rapidly over the last decade, and biotech and pharmaceutical companies have also invested heavily in ovarian, uterine, and endometrial health, with many novel therapeutics seeing early success in clinical trials.

The lab has already made enormous progress in finding ways to model and identify markers for endometriosis, and the team is fueled by a passionate commitment to bringing tangible advances to patients in the coming years. Beyaz says their vision is to create a dynamic synergy between basic research and the clinic to transform a disabling chronic illness into a condition that clinicians can help patients manage and hopefully end in the near future.

“I know that’s very ambitious,” says Dr. Beyaz, “but if you are not going to shoot for the stars, why start the journey?”