Dr. Maria Rovito didn’t set out to be an endometriosis historian; as a college student, she intended to pursue journalism. When she began experiencing intense pain and gastrointestinal issues during her time at university, she had no idea that she was at the start of an entirely new career path.

“When I was diagnosed with endometriosis at 25 years old, I just couldn’t understand why it had been so hard to get a referral to a surgeon,” Dr. Rovito says. “People think, ‘Period stuff? I don’t want to hear about it.’ It really pissed me off.”

At the time, Dr. Rovito had just begun her PhD program in philosophy at Penn State. Her program required her to complete a dissertation, and soon she made the decision to center her research around her own experience seeking care for her endometriosis.

Throughout her studies, Dr. Rovito had found kinship with authors who addressed women’s health. "Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar? She’s a 21 year-old college student and all of her distress and suffering is ignored by the medical system.” Virginia Woolf’s work, Jane Eyre, and other staples of feminist literature directly influenced how Dr. Rovito interacts with the endometriosis community today.

As both patient and student, Dr. Rovito also frequented social media groups full of other people with endometriosis. She started to recognize patterns: misdiagnosis, dismissal, loss of livelihood due to symptoms. Dr. Rovito spent four years studying these patterns while visiting medical libraries throughout her dissertation. The more she read on the history of endometriosis, the more she understood that these patterns were as old as endometriosis itself.

“I thought, “‘Holy hell, why has no one written the history of this disease?’ The gaslighting is not new. It’s basically been happening since the start of medicine.”

To research historical treatments of endometriosis, Dr. Rovito had to cast a wide net when searching through the archives. Though the disease is not new, the term 'endometriosis' wasn't coined by Dr. John Sampson until 1925. “[When researching], I started with ‘dysmenorrhea,’ since it is one of the primary symptoms, and I found that many of the case studies and texts connected it to GI issues, infertility, and ‘mania’ and ‘neuroses.’ That gave me a clue about why so many patients are misdiagnosed with depression or anxiety before they are given their diagnosis today,” Dr. Rovito says. She continued her research with terms like “hysteria,” “mania,” and “catamenia” to connect these narratives together.

Dr. Rovito recalls one medical study about surgical endometriosis care from the mid-20th century that specifically referenced using lobotomies as treatment for dysmenorrhea (1). “Finding it was perhaps the piece of the puzzle that put everything together: why so many patients today are viewed as ‘hysterical’ or that they’re ‘making everything up for attention,’” Dr. Rovito explains. “But this [attitude] started in ancient Greece with the wandering womb.”

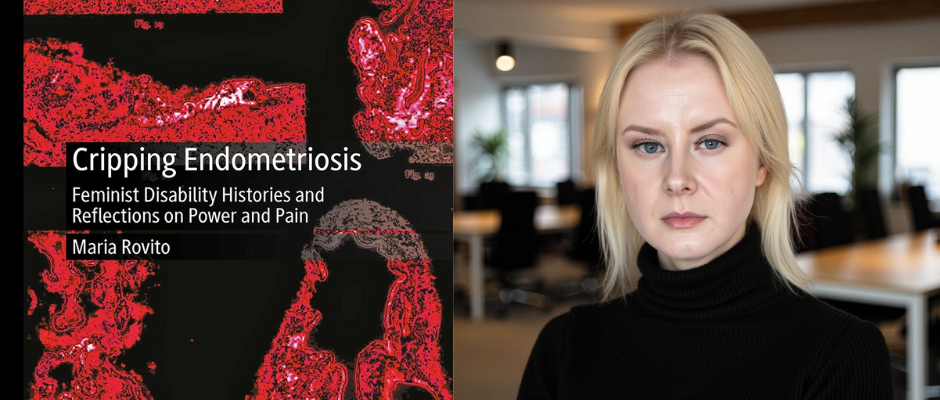

Today, as an adjunct professor at the Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Dr. Rovito is anticipating the release of her book, Cripping Endometriosis: Feminist Disability Histories and Reflections on Power and Pain. The book explores the ways that historical perceptions of endometriosis led to the mistreatment of countless patients.

Much of Dr. Rovito’s work examines how endometriosis became known as the ‘career woman’s disease’ and interrogates the long-term consequences of that designation. As she explains, “Society in the late 19th century feared that women with careers were postponing childbearing. They saw endometriosis as a punishment for holding off on marriage and kids.”

The common understanding of endometriosis during the late 19th century also positioned the disease as primarily affecting heterosexual white women, which in turn dismissed every other group of people affected. This misperception still endures, influencing endometriosis care today.

“Think about all the other populations that are affected by endo: women of color, women who aren’t sexually attracted to men, teenagers, trans and nonbinary people. How many people are still medically gaslit today because of that narrow idea of the 19th century ‘career woman?’”

But why else do the stereotypes and misinformation persist? Dr. Rovito believes that many of the delays in diagnosis patients go through are directly tied to associations with endometriosis being a ‘period disease.’ At the time Dr. Sampson posed his theory of retrograde menstruation in the 1920s, physicians still weren’t sure how endometriosis lesions developed in the body. While the theory of retrograde menstruation is widely accepted today, Dr. Rovito points out that it does not mean endometriosis is purely a reproductive disorder, and that the association with menstruation may actually be hurting patients.

“What about endometriosis on the lung or the heart or brain? Endo affects how people pee and what foods they can eat. Medically, Sampson’s influence was so profound that some physicians still ignore [non-gynecological] symptoms today.”

Dr. Rovito is concerned about how few of her students are intending to pursue gynecology as their specialty. This small number could be in part due to a perceived stigma about working in women’s health, likely influenced by the centuries of misinformation and the systematic dismissal of women’s health concerns. Historically, endometriosis has been downplayed by the medical community, and this has impacted the level of importance the average physician today continues to place on the condition. “Moving [endometriosis] out of OBGYN into other specialties might help us take it more seriously,” Dr. Rovito says, emphasizing the importance that these other specialities are well-versed in endometriosis education and recognition.

This idea is a profound and even controversial shift in the way we think about endometriosis, but it mirrors the way other chronic illness patients receive care. Many patients with chronic illnesses are supported by entire care teams familiar with their condition. Those physicians all work together with the understanding that one symptom influences the other. Shifting endometriosis into other fields beyond gynecology could help doctors of all specialties become more acquainted with the clinical markers and ensure patients go to the right place for treatment. Patient experience could look dramatically different. Some patients will never be able to afford surgery, or undergo surgery, and even once a patient is treated surgically, endometriosis can continue to be a chronic pain issue. In this framework, gastroenterologists, for example, might feel more confident treating endometriosis-related constipation symptoms rather than redirecting their patient back to a gynecologist.

Dr. Rovito also believes that tying endometriosis to periods and infertility rather than chronic pain makes people believe the condition isn’t that serious. “People think, ‘An infertility disorder? You can still work. You don’t need legal protections.’” This misperception impacts endometriosis’ classification as a disability. As of 2026, endometriosis is still not officially classified as a disability by the Americans with Disabilities Act, despite the disease’s impact on daily life.

Though she recognizes that fertility is often a major concern for those living with endometriosis, she calls for a more patient-centered approach by care teams. “I want physicians to recognize that my life, my current life as it is right now, is more important than any potential children I could have in my future. We need [the medical community] to recognize the pain and suffering that endo causes first.”

Dr. Rovito’s research also shed light on Dr. Sampson’s influence on endometriosis care. “Dr. Sampson stated later in his life that implantation theory was just that—a theory—and if it was proven wrong, his theory should follow him to the grave. With the newer models of how endometriosis might form—including cellular metaplasia, environmental factors, genetics, and faulty embryonic development—I wonder how Sampson might feel about how his work has affected research and treatment today.”

Dr. Rovito is determined to help the medical community at large understand that endometriosis is a severe chronic pain disease that has impacted the lives of countless people long before modern medicine ever became aware of it—an impact that has subsequently played a critical role in shaping societal expectations for women throughout history. Her writing has already become part of the literary catalogue for future endometriosis historians, simultaneously paving a road that honors the legacy of everyone who has been dismissed, medically gaslit, or misdiagnosed, while also building towards a future without the barriers and stigma that let endometriosis walk unseen for so many centuries.

Dr. Rovito’s forthcoming book, Cripping Endometriosis: Feminist Disability Histories and Reflections on Power and Pain will be released in March 2026 by Palgrave MacMillan.

1 Selverstone, Bertram, and James C. White. 1950. Surgical treatment of the pain of pelvic disease. In Progress in gynecology, ed. Joe V. Meigs and Somers H. Sturgis, vol. II, 748–761. New York/Boston, MA: Grune and Stratton. Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Library Rare Books, Harvard Medical School.