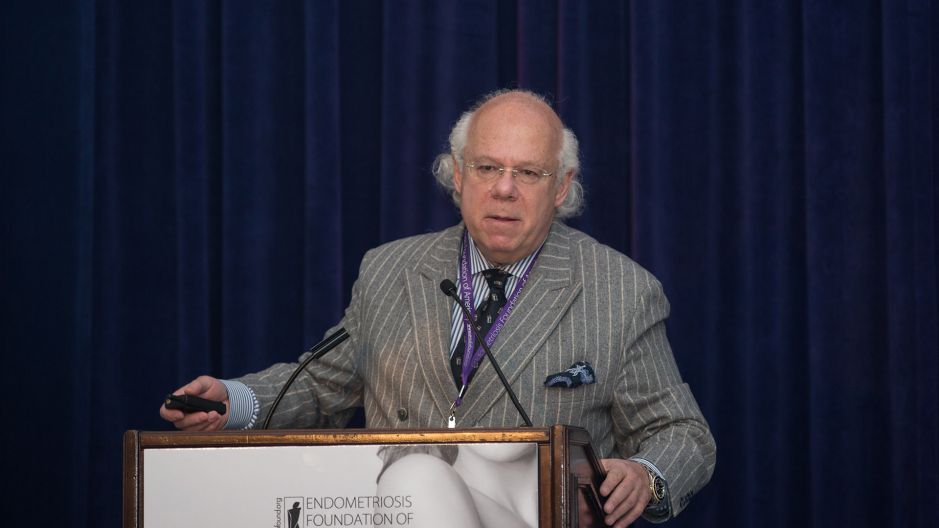

Endofound Medical Conference 2017 "Breast, Ovary and Endometriosis" October 28, 2017 - Lotte New York Palace Hotel

Norbert Gleicher, MD, FACOG, FACS.

Center for Human Reproduction

Interviewer: Well thank you so much for joining us today. Please tell people your title.

Norbert Gleicher: I am Medical Director and Chief Scientist at the Center for Human Reproduction.

Interviewer: Okay, thank you. And you just put out an amazing article about abnormal embryos and there kind of being new life for them. Kind of summarize this article for us, please.

Norbert Gleicher: I assume you're referring to the article that appeared in New York Magazine?

Interviewer: Yes, yes.

Norbert Gleicher: I was just one of the many involved parties in this article. There's a procedure, which in recent years has become increasingly popular, mostly in the United States, less so elsewhere in the world. It used to be called until recently, preimplantation genetics screening or PGS. And recently received a new name, it is now called preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploid PGTA. And the hypothesis behind this procedure, which is done in association with in vitro fertilization, is that by testing whether embryos are chromosomal normal or abnormal. And by excluding so called abnormal embryos one would improve pregnancy rates for the remaining embryos, reduce miscarriage rates, speed up time to pregnancy, etc., etc. And this is a hypothesis that superficially on first impression sounds very attractive, very logical.

But unfortunately, in over 15 years of use of different forms of this procedure has never been able to demonstrate that it really fulfilled any of these promises. And so we have gone from one technology, to the next technology, now to a third round of technologies, always assuming that the reason why we don't see the promised improvements must have something to do with the technology or inadequate technologies that have been used. And this has been also very aggressively pushed by the genetic testing industry, which obviously has a strong economic interest in doing as many tests as possible. A small number of IVF experts both in this country and in Europe, amongst them myself and my colleagues at Ellis Center, however have been arguing now for over 10 years that the problem with PGS is not the technology. The problem with PGS is the basic concept.

And we have been arguing that the basic biology of an early stage embryo simply does not allow this test to be successful in fulfilling the promise of improved pregnancy chances, etc. And the reason for that is principally the fact that we have learned over the last few years that most early stage embryos are what is called mosaic. Mosaic means that there is more than one cell line in an organ, in a tissue, or in a tissue for that fact. Embryos as we now understand, especially in their trophectoderm, which is the outlier of an embryo at blastocyst stage. And that is where we take the biopsy to find out whether the embryo is chromosomally normal or not, especially that trophectoderm it appears is in a high percentage or embryos, and some people say in all embryos mosaic. Meaning, the trophectoderm is basically populated by one cell line in the majority, but then there are islands of other cell lines possible.

And when you imagine that in a three-dimensional picture, almost like soccer ball where you have black and white squares. What your result will be from a biopsy of a tiny few cells from that trophectoderm will depend where you take the biopsy. And so up until now many proponents of the procedure still argue that grabbing five, or six cells, or seven cells are representative of the whole trophectoderm. But that doesn't make any sense if one really recognizes that it is almost universal that there are other islands on that globe often including just a few cells. But if you grab one of those few abnormal cells under the current interpretation it means your interpretation is that everything is abnormal. This maybe just be a tiny little island and everything else may be normal, so that's the first problem.

The second problem is again, a basic biological issue that the trophectoderm from where we take the biopsy has really nothing to do with the fetus, with the baby. The trophectoderm becomes the placenta. The baby, the fetus, comes from a different part of the embryo, which is called the inner cell mass, which is inside this globe and which we do not biopsy. We are basically taking a biopsy from the very early placenta in order to find out how the very early fetus is. And that also doesn't make any sense because we have known for 30, 40 years that you can have totally normal babies born and if you do pathological slicing of the placenta you will find islands of chromosomally abnormal cells. That's the second reason why this doesn't work.

The third reason is maybe even biologically the most interesting, though also the most controversial because it is very difficult to prove this in human experimentation for ethical reasons. But in animal models, it has been demonstrated that embryos what we call downstream from blastocyst stage, meaning later on can to a very significant degree self correct. Meaning that chromosomally abnormal cells commit suicide, they die off while the normal cells continue growing. Even if the embryo at those early stages where we take biopsy's, even if it is for real chromosomally abnormal, unless it is throughout all cells chromosomally abnormal, many of these embryos can apparently still self correct down the road. And therefore, it would be like in a newborn baby to predict who will be obese and will not be obese, obviously something that we cannot do.

We have now a much better understanding of the biology of early embryos, which tells us that this test simple doesn't make any sense. Therefore, at least people like me who have long argued that the test doesn't make any sense, have more data to support it. While the proponents of the test are somewhat on the defensive because we were the first ones who starting in 2012, because we were convinced that this test is basically useless, we started transferring embryos that our genetics colleagues who did those test had declared as abnormal. And therefore, which would be discarded. And low and behold, we have close to 10 pregnancies and healthy babies from such transfers. And worldwide, close too pregnancies, healthy pregnancies from such transfers. There is more and more evidence that this is a really useless test.

Interviewer: Going forward, what happens now? Does this become something that's kind of made this standard that you don't discard the "abnormal embryos?" How does this change things?

Norbert Gleicher: It changes practice we believe in many, many different ways. First of all, it raises the question whether this test should at all be done because what is now also increasingly apparent is that there's so many false positive cases. Meaning so many potentially normal embryos are being discarded that at least in some women, particularly women who have very few embryos in their IVF cycle, the test actually reduces their chances. If a woman has 15 beautiful embryos, and you by mistake discard three or four, it's obviously not a good thing. But it will not impact her pregnancy chance because she still has a lot of good embryos left. If you take an older woman or a younger woman with premature ovarian aging who has only three or four embryos, if you discard three or four embryo's by mistake, she has no embryos left for transfer. And those were exactly the patients where we started our experiments of transferring, those were all women who had supposedly no normal embryos in the whole cohort during an IVF cycle.

The first impulse is obviously to say don't do the test. And my own personal opinion is that as this knowledge starts to be distributed and this article in New York Magazine was very, very helpful because it was an objective description of both sides of this divide. I think there will be much less PGS ordered. But on the other hand, we are obviously also facing an industry, which is making a lot of money from this test. And which therefore, is still strongly advocating it and spending a lot of money on marketing.

This raises the question when for example the Food and Drug Administration will come into this discussion because this is really a test where, according to a study recently published by the current President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. In his opinion, roughly 40% of good embryos are discarded by mistake. That about that, it's a huge negative medical effect. I think the numbers will decline. And hopefully there will be some intervention, either from the ASRM or from the FDA, which will simply come out with a statement and say things are such and such, And that you have better evidence that what you are doing, please stop.

Interviewer: You spoke about, for example a woman who may have a mature ovarian age or may not have a lot of embryos, just a few, a handful. What has your experience been when you've been able to transfer a "abnormal embryo" and the pregnancy to term and it's a healthy baby. What is that like seeing this woman have a chance of having a baby when otherwise, she may have been turned away?

Norbert Gleicher: If you speak to those people they are beyond grateful, but they often also are quite angry. Because their decision to have these embryos transferred is not an easy one because they are hearing two dramatically opposing sides. Both credible people, or credible institutions, both scientists often who are working in the field and who have excellent reputation. And they're hearing completely opposing opinions. This is never an easy decision for patients, and I can tell you after having done by now probably 15 or so of these transfers, this is usually truly a last chance decision. In other words, they usually have done everything they can. They can afford, they can mentally afford, financially afford, and they say okay before I accept that I need donor eggs or that I will have no children, let's try this as a last resort. It's conflicted for them, but obviously when it succeeds they are beyond happy.

Interviewer: Thank you so much for your time. It is a very interesting topic that I'm sure we're going to be hearing lots more about in the future. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today.

Norbert Gleicher: My pleasure.